The Staff Engineer's Path

Book Summary

Job titles do matter

- Helping People Understand Their Progression

- Titles help employees see their growth and career development within an organization. They serve as markers that indicate where someone is in their professional journey. For example, progressing from "Junior Developer" to "Senior Developer" gives a clear indication of growth in skill and responsibility. It allows employees to understand their current standing and what they need to do to reach the next level. This clarity can be motivating and help with setting personal and professional goals.

- Vesting Authority in Those Who Might Not Automatically Receive It

- Titles can grant authority to individuals who might not naturally be seen as leaders or decision-makers. For example, if someone is titled "Lead Engineer," others in the organization will recognize their leadership role, even if they might not initially see themselves as a leader. It ensures that the right people are respected for their expertise and positions, which is especially important when working with cross-functional teams or newer team members who may need recognition for their contributions.

- Communicating an Expected Competency Level to the Outside World

- Titles help convey to people outside the organization what skills and level of experience someone possesses. For example, when interacting with clients or external partners, a title like "Principal Engineer" or "Director of Engineering" can communicate a high level of expertise and authority. It builds trust and credibility with clients, stakeholders, or partners, helping them understand the experience level of the individuals they are working with. It can also be crucial during recruitment, as candidates can gauge the seniority and expectations of a role.

What is a staff engineer

- An engineers who can see the big picture

- An engineer who lead projects that cross multiple teams

- An engineer who is a good influence

Staff engineers should do this big-picture, big-project, good-influence stuff, but here’s the problem: they can’t do it on top of the coding workload of a senior engineer. Any hour you’re writing strategy, reviewing project designs, or setting standards, you’re not coding, architecting new systems, or doing a lot of the work a software engineer might be evaluated on. If a company’s most senior engineers just write code all day, the codebase will see the benefit of their skills, but the company will miss out on the things that only they can do. This kind of technical leadership needs to be part of the job description of the person doing it. It isn’t a distraction from the job: it is the job.

What is my job?

- You’re Not a Manager, but You Are a Leader

- As you increase in seniority, you’ll take on bigger projects, projects that can’t succeed without collaboration, communication, and alignment; your brilliant solutions are just going to cause you frustration if you can’t convince the other people on the team that yours is the right path to take. And whether you want to or not, you’ll be a role model: other engineers will look to those with the big job titles to understand how to behave. So, no: you can’t avoid being a leader.

- Be a good leader. See Kind Engineering

- You’re in a “Technical” Role (Not coding role)

- At this level, your goal is to solve problems efficiently, and programming will often not be the best use of your time. It may make more sense for you to take on the design or leadership work that only you can do and let others handle the programming. Staff engineers often take on ambiguous, messy, difficult problems and do just enough work on them to make them manageable by someone else. Once the problem is tractable, it becomes a growth opportunity for less experienced engineers (sometimes with support from the staff engineer).

- You Aim to Be Autonomous

- At staff+ levels, your manager should be bringing you information and sharing context, but you should be telling them what’s important just as much as the other way around

- Autonomy demands responsibility. If the thing management asked you to work on turns out to be harmful, you have a responsibility to speak up. Don’t silently let a disaster unfold. (Of course, if you want to be listened to, you’ll have to have built up a reputation for being trustworthy and correct.)

- You Set Technical Direction

- Underlying the product or service your organization provides is a host of technical decisions: your architecture, your storage systems, the tools and frameworks you use, and so on. Whether these decisions are made at a team level or across multiple teams or whole organizations, part of your job is to make sure that they get made, that they get made well, and that they get written down

- You Communicate Often and Well

- The more senior you become, the more you will rely on strong communication skills. Almost everything you do will involve conveying information from your brain to other people’s brains and vice versa. The better you are at being understood, the easier your job will be

Understanding your role

Where in the organisation you sit.

Reporting chains will affect the level of support you receive, the information you’re privy to, and, in many cases, how you’re perceived by colleagues outside your group.

Reporting High vs Reporting Low

Reporting to a higher-level manager, like a director or VP, offers a broad perspective and valuable learning opportunities from experienced leaders. However, you may get less time and attention from them, potentially impacting support and advocacy for your work. Conversely, reporting to a lower-level manager provides more focused attention and better advocacy, but may limit your influence within the organization and access to broader information. It’s important to balance these dynamics based on your career goals and ensure alignment with your manager's priorities. If misalignment persists, consider advocating for a reporting change.

What's your scope

Your reporting chain influences the scope of your responsibilities and the areas you focus on, even without a formal leadership role. Within your scope, you should have a say in both short-term and long-term goals, be aware of major decisions, and help guide the growth of other engineers. While your manager may expect you to focus mainly on their domain, you might also be involved in broader organizational challenges. Be clear about your scope but remain adaptable, especially during crises, as being a staff engineer often means stepping beyond your defined responsibilities to address urgent issues.

A scope too broad

When your scope is too broad or undefined, several issues can arise:

- Lack of Impact: If everything can be your responsibility, it's easy to get pulled into numerous side projects, spreading yourself too thin and failing to achieve meaningful results.

- Becoming a Bottleneck: As the go-to person for every decision, you may slow down the organization by being required for every discussion, rather than accelerating progress.

- Decision Fatigue: Even if you avoid taking on every task, you'll constantly need to decide what to prioritize, which can be draining.

- Missing Relationships: Working across many teams can make it difficult to build the strong relationships that facilitate smooth collaboration and mentorship.

It’s better to focus on a specific area, build influence, and achieve successes before moving on to new challenges. This approach ensures more meaningful impact and better work relationships.

A scope too narrow

Scoping yourself too narrowly as a staff engineer, such as being dedicated to a single team, has benefits but also risks:

- Lack of Impact: You might focus on areas that don’t require the expertise of a staff engineer. It’s important to ensure the team or technology is crucial to the company.

- Opportunity Cost: Being focused on one team might limit your visibility for solving broader issues across the organization.

- Overshadowing Other Engineers: You may dominate technical discussions, taking away learning opportunities from less experienced engineers.

- Overengineering: With less work, you might create overly complex solutions for simple problems.

While some projects are deep enough to justify this focus, it’s essential to be clear if you’re in such a space to ensure your skills are effectively used.

What shape is your role?

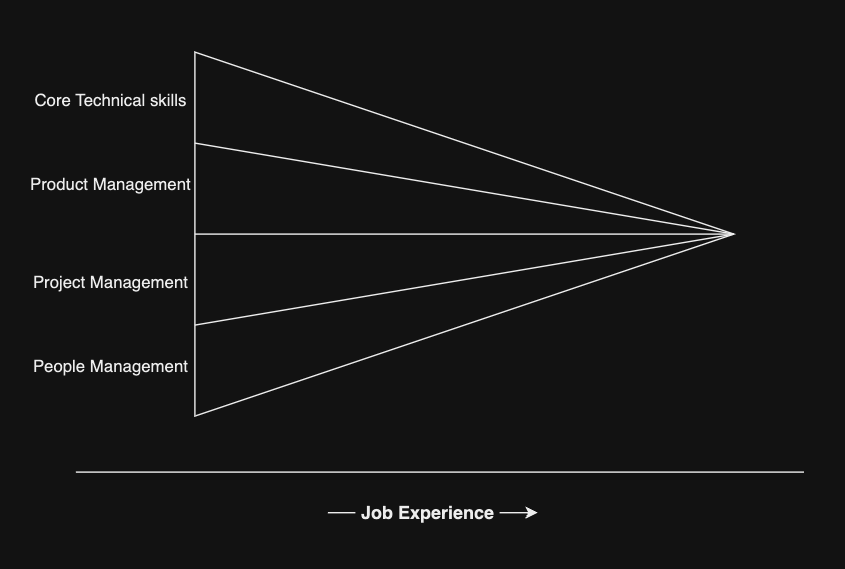

Four disciplines that are needed in any job in the world

- Core technical skills

- Coding, litigation, producing content, cooking—whatever a typical practitioner of the role works on

- Product management

- Figuring out what needs to be done and why, and maintaining a narrative about that work

- Project management

- The practicalities of achieving the goal, removing chaos, tracking the tasks, noticing what’s blocked, and making sure it gets unblocked

- People management

- Turning a group of people into a team, building their skills and careers, mentoring, and dealing with their problems

The more senior you get, the more this becomes true, the more and more there is an expectation that you can shift across each of these four kinds of jobs easily and fluidly, and function in all rooms.

How much do you want (or need) to code?

As staff engineers advance in their careers, they might find themselves coding less and focusing more on broader responsibilities like architecture or influence. Some still contribute code daily, while others review code or take on smaller, less critical coding projects to stay sharp. If you need to be hands-on with code regularly, avoid roles that focus heavily on strategy or architecture, or have a plan to stay engaged with coding while managing larger responsibilities. This helps avoid getting distracted by coding tasks at the expense of addressing bigger challenges.

How’s your delayed gratification?

Coding has comfortingly fast feedback cycles: every successful compile or test run tells you how things are going. It’s like a tiny performance review every day! It can be disheartening to move toward work that doesn’t have any built-in feedback loops to tell you whether you’re on the right path.

What’s Your Primary Focus?

Every time you choose what to work on, you’re also choosing what not to do, so be deliberate and thoughtful about what you take on

What's important?

Early in your career, if you do a great job on something that turns out to be unnecessary, you’ve still done a great job. At the staff engineer level, though, everything you do has a high opportunity cost, so your work needs to be important.

Know why the problem you’re working on is strategically important—and if it’s not, do something else.

What needs you?

Try to choose a problem that actually needs you and that will benefit from your attention